Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia

Neurological and Physiological Findings

Chapter 9 of 12 · Pages 237–273

Neurological and Physiological Findings

Morbid Anatomy

Agostini also reports some traces of arrested development and residua of childish diseases. Mondio found in six cases anomalies in the convolutions, which he regards as signs of degeneration. Schroder from the same point of view describes in one case displacement of Purkinje cells and double nuclei, and also syncytial formations in the pyramidal cells of the cerebral cortex.

Fig. 36. Nerve-cells surrounded by glia nuclei.

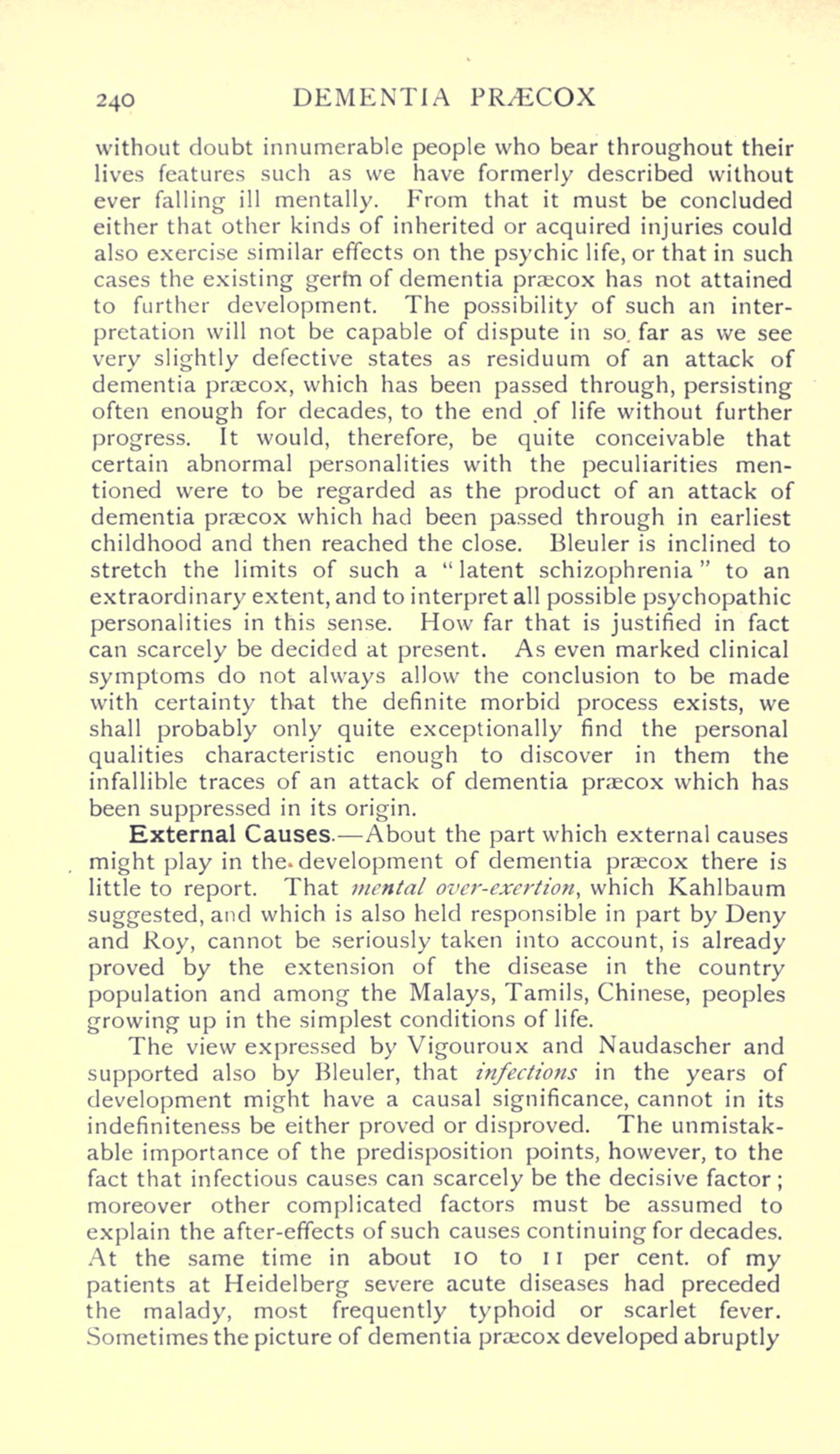

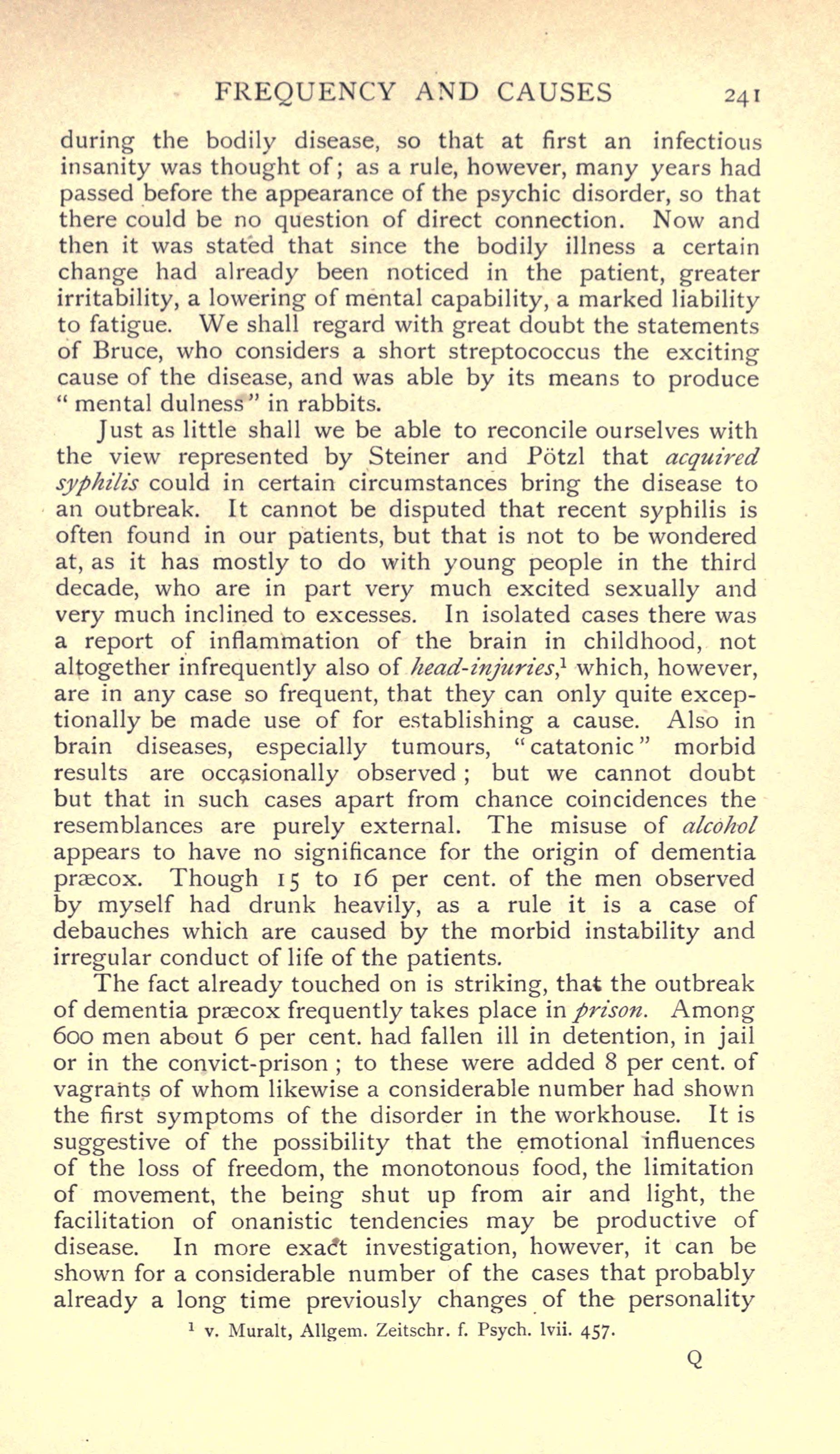

The accompanying figures represent some of the most important findings in dementia praecox. The first two figures represent acute changes. In Fig. 36 a number of nerve-cells from the deep layers of the cortex are reproduced, which are surrounded as thickly as possible by numerous glia cells recognizable by their dark nuclei, some of which have very much enlarged protoplasmic bodies. The distribution of decomposition products is represented in Fig. 37, which is taken from the cortex of a stuporous patient who died suddenly in a seizure. Two glia nuclei (a) are seen, round which are grouped radiating chains of fine granules; these are fibrinoid granules which have accumulated in the far-branching protoplasmic bodies of the glia cells which are otherwise not recognizable here. The lower glia nucleus lies on the nucleus of a nerve-cell (a) still partially visible; in the neighbourhood of the upper nucleus also there is a nerve-cell (a).

Fig. 37. Fibrinoid granules in glia cells.

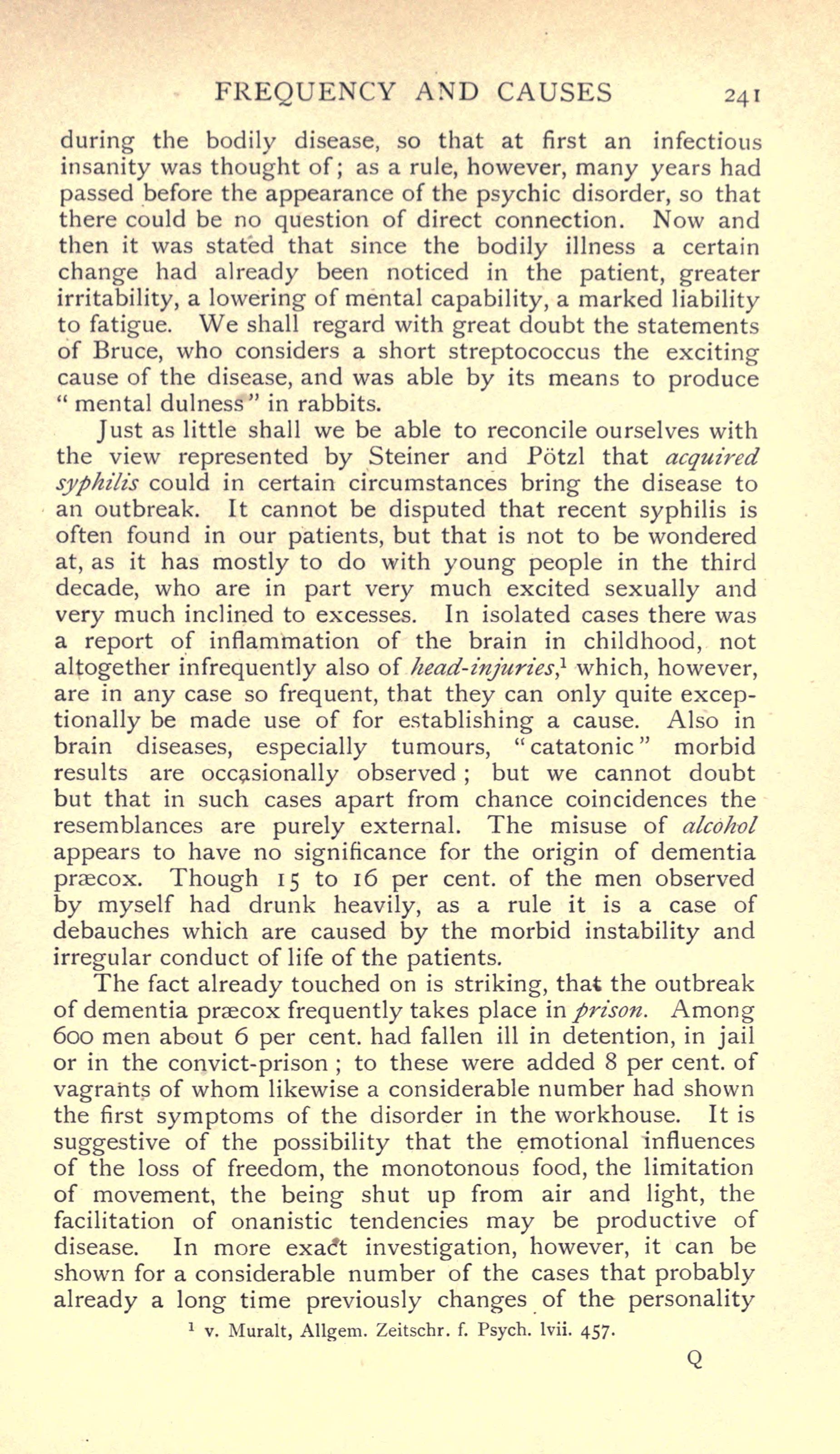

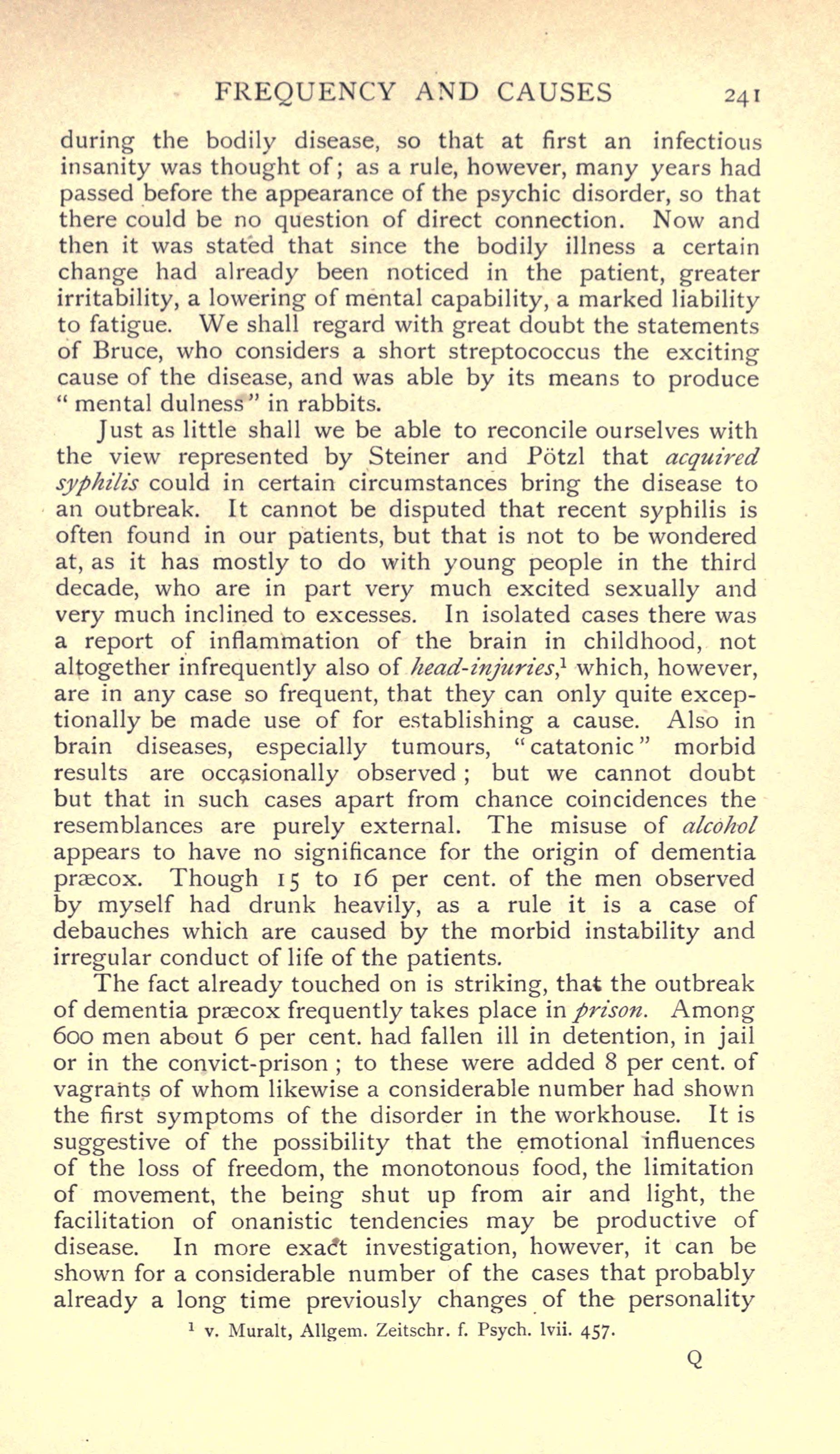

The chronic changes in the nerve cells are reproduced in the two following figures. In Fig. 38 three nerve-cells from the upper part of the third layer of a healthy frontal lobe are represented; beside these there are two normal glia nuclei. In contrast to that three cells from the corresponding part of the cortex of a patient who died after long duration of dementia praecox in his twenty-fifth year are seen in Fig. 39. The narrowed shrunken cells with dark, long-drawn-out nuclei and deeply stained processes exhibit the picture of cell-sclerosis; the tissue arranged as a network contains lipoid products of disintegration. Of the glia nuclei lying beside them one is unusually large; the other two are small and darkly stained (pyknotic). In Figs. 40 and 41 also there are healthy and diseased nerve-cells placed in contrast. In two of the healthy cells and in one of the two glia cells lying between them there are only a few fine lipoid droplets. The drawings are from the third layer of the frontal lobes of a woman thirty-seven years of age who was mentally sound.

Fig. 38. Normal nerve-cells with glia nuclei.

Fig. 39. Sclerotic nerve-cells in dementia praecox.

In contrast we see the diseased cells, changed in the highest degree; they were taken from the cortex of a man twenty-three years of age who had suffered for five years from dementia praecox. In consequence of the distortion of the cortical structure caused by the morbid process some of the cells are obliquely placed; their nuclei are shrunken and elongated, their processes are recognizable for a long way. But above everything one sees the shapeless, turgid body of the cells and also the processes completely filled with lipoid products of disintegration. Here also there meet us two unusually large glia-nuclei along with a small dark one; the cell-bodies of these, which otherwise are not visible, show numerous lipoid granules.

Fig. 40. Healthy nerve-cells. Fig. 41. Nerve-cells diseased in high degree filled with lipoid products of disintegration.

As in the clinical picture of the disease there are apparently also in the anatomical findings two different groups of processes, first the morbid disorders caused directly by the disease, and second the losses remaining as a consequence. To the first belong the changes in the cells, the formation of products of disintegration, the hyperplasia of glia, especially the appearance of amoeboid glia cells; to the second the destruction of cells and fibres, the necrotic and involutionary phenomena in nerve-tissue and glia, the deposition of fat and pigment. According to whether it is a recent case relatively, an acute relapse of the disease, or an old case in the terminal state when the disease has long since run its course, the combination of anatomical changes will be different.

It has been already mentioned that the loss is for the most part to be found in the second and third cortical layers. Whether it extends over wide cortical areas to the same degree, remains still to be investigated; by some investigators, Mondio, Zalplachta, Agostini, De Buck and Deroubaix, Dunton, Wada, it is stated that it involves the frontal lobes and the area of the central convolutions, also the temporal lobes to a greater degree than the occipital cortex. Klippel and Lhermitte report atrophic changes also in the cerebellum.

In the remaining organs of the body in general only the findings resulting from the chance cause of death can be found. Dide, who looked for changes in the sexual glands, found these healthy, but on the other hand often saw fatty degeneration of the liver. Benigni and Zilocchi describe two cases with diffuse fatty degeneration in the liver, kidneys, heart, vessels, thyroid gland, and hypophysis. It must in the meantime remain undecided whether such findings have any further significance.

Relation of Morbid Anatomy to the Clinical Picture

If we now make the attempt to consider the relation of the anatomical findings which hitherto have been got, to the clinical picture of the disease, there are two points which might be considered significant, the distribution of the morbid changes on the surface of the cortex, and the share of the different layers of the cortex. If it should be confirmed that the disease attacks by preference the frontal areas of the brain, the central convolutions and the temporal lobes, this distribution would in a certain measure agree with our present views about the site of the psychic mechanisms which are principally injured by the disease. On various grounds it is easy to believe that the frontal cortex, which is specially well developed in man, stands in closer relation to his higher intellectual abilities, and these are the faculties which in our patients invariably suffer profound loss in contrast to memory and acquired capabilities. The manifold volitional and motor disorders, which extend partly to the harmonious working of the muscles, will make us think of finer disorders in the neighbourhood of the precentral convolution. As it does not go so far as paralyses or to genuine apractic disorders, and there are only indications occasionally of motor-aphasic disorders, we may assume, although as yet no investigations on the subject are to hand, that the actual motor discharging-stations are not attacked by the destructive process. On the other hand the peculiar speech disorders resembling sensory aphasia and the auditory hallucinations, which play such a large part, probably point to the temporal lobe being involved. Here also, however, there is no true auditory aphasia, but only a weakening of the regulating influence of clang-association on the movements of speech expression, perhaps also a loosening of the connection between the former and conceptions; we must, therefore, imagine that the disorder is essentially more complicated and less circumscribed than in sensory aphasia. The auditory hallucinations, which exhibit predominantly speech content, we must probably interpret as irritative phenomena in the temporal lobe; it might not be due to chance that we invariably observe them along with confusion of speech and neologisms. The phenomena of hallucinatory repetition and hearing of thought point to the relations between ideas and sensory areas being attacked by peculiar disorders.

As the significance of the cortical layers is at present still almost wholly unknown, it will scarcely be possible to set up hypotheses with regard to the influence of the site of the morbid processes in definite layers, although it is certainly not indifferent for the form of the disease. According to the extended experience of Alzheimer we may assume that the permanent loss of nerve-tissue capable of work concerns preferably the second and the third layer of the cortex, therefore the smaller nerve-cells, though in the acute periods of the malady a severer attack of the deeper layers is simulated by the proliferation of glia which is there specially conspicuous. On the other hand the first terminal stations of the paths radiating from the sense-organs into the cortex and the large motor cells, in which we locate the origin of the pyramidal tracts which make their way to the spinal marrow, both lie in the depth of the cortex the structure of which, moreover, still most resembles that of the cortex of the lower animals. In these layers, therefore, will the processes presumably take place, which correspond, on the one hand to the appearance of a sensory perception, on the other hand to the discharge of a motor impulse, or are immediately connected with these.

In opposition to this we may ascribe to the upper small-celled layers such activities as are peculiar to the higher psychic stages of development since they reach their highest perfection in man, especially in the frontal lobes. Though it would not be suitable to put forward conceptions going into particulars about these relations, still it is easy to think before everything of the process of abstraction, which transforms perceptions to general ideas, sensations to emotions, impulses to permanent trends of volition. These abstract creations of the higher psychic activity are what the essence of the psychic personality is compacted of. As a permanent deposit of the experiences of life they dominate the thought, feeling and will of man for long periods, and up to a certain degree make it independent of the experiences of the moment, which through it are reinforced, moderated, corrected, or in certain circumstances even shown to be false. One may probably with impunity lay stress upon the fact, that in dementia praecox apparently it is the loss of those permanent foundations of the psychic life, as they are created by abstraction, which influences the clinical picture often in the highest degree in incoherence of thought, in contradictory change of emotions, in impulsiveness of action.

The small-celled layers extend in fairly uniform structure over nearly the whole surface of the brain. The hypothesis, therefore, is easy that besides the task of abstraction, perhaps in connection with it, they have also the task of mediating between the activities of the deeper layers which are more confined to circumscribed areas, especially sensory perceptions and volitional impulses. The real psychic elaboration of external experience, the linking of it on to past experiences, the critical judgment of it by means of formerly acquired standards, the connecting of it to new psychic structures, to conclusions and creative ideas, could even so be ascribed to an organ gathering things together in that way, as the preparation for action by weighing values, the ripening of decisions on the ground of deliberation. It is evident that the activities named here must before everything else be regarded as foundations of the inner unity and consistency of the psychic life. The fact that the working of external influences is essentially determined by the permanent character of the personality concerned, and that in the other direction action represents the outflow of the whole experience of life, necessarily forces us to the assumption, that the organ of our psychic life must also contain mechanisms which mediate a general connection of all the psychic workshops among each other. Just the destruction of the psychic personality, of this inner harmony of all the parts of the psychic mechanism in perhaps even surprising individual activities is, as formerly demonstrated, the real fundamental disorder in dementia praecox. If Alzheimer’s finding is proved to be invariably present, we might from it conclude with a certain probability that in the small-celled layers, that harmonious gathering into one of psychic activities takes place, the destruction of which characterizes dementia praecox.

This hypothesis gains great support from the circumstance, that in our disease the lower psychic mechanisms as a rule are comparatively little encroached on, corresponding to the slighter damage done to the deeper cortical layers. The power of purely sensory perception remains often fairly well preserved, as also the memory of perceptions, and acquired knowledge and skill. On the other hand judgment is lost, the critical faculty, the creative gift, especially the capacity to make a higher use of knowledge and ability. Pleasure and the lack of it are often perceived by the patients with the greatest intensity, but the sense of beauty, the joy in understanding, sympathy, tact, reverence, desert them, as also the intelligent, continuous emotional relations to the events of life. The patients may also exhibit volitional activity of the greatest strength and endurance, but they are wholly incapable of arranging their lives according to rational principles or of consistently carrying out a well-considered plan. We see, therefore, in all the domains of psychic life the ancestral activities offering a greater power of resistance to the morbid process than the psychic faculties belonging to the highest degrees of development, corresponding to the slighter damage done to the deeper cortical layers which are more like those of the lower animals, in contrast with those which only attain to development with the appearance of the most complicated psychic activities.

The transparency of this relation is somewhat clouded by the fact, that memory being well preserved may make possible the continuance of individual capabilities which are much exercised. We may well assume that the site of both sensory and mechanical memory is to be sought for principally in the deeper cortical layers, the former in the sensory centres, the latter in the areas which mediate the harmony of movements. The experience which has been formerly acquired is able up to a certain point to cover the destruction of the higher faculties, just so far as independent psychic activity may be replaced by acquired proficiency. Precisely work which is dependent on understanding is often served by associations of ideas and habits of thought which have been firmly laid down in forms of speech, while in the domains of the emotional life and of action an adjustment to the special conditions of the given moment is requisite in far higher degree. Perhaps there lies in this an essential ground for the clinical experience, that the disorders of dementia praecox usually appear here earlier and in more severe form than in intellectual activities.

But further by the destruction of the harmonious personality which holds together and dominates the whole psychic life, there is given to the influence of ancestral mechanisms a free play which they could never otherwise acquire. To these namely I reckon the activities of automatic obedience and negativism, which are not set in motion by deliberation or moods, but appear and disappear irregularly. Stereotypy also, as a general expression of the facilitating action of volitional impulses, might come in here, as also the rhythmic movements characteristic of profound idiocy. Lastly in the mannerisms and derailments of action one might see the consequence of defective consciousness of purpose and defective precision of volitional impulses, which makes them more easily accessible to all kinds of side-influences. Similarly neologisms and the manifold disorders in the structure of speech may probably be connected with loosening of the connection between abstract ideas, speech sounds and speech movements and with defective characterization of speech formulae; all these are disorders which may be brought under the general point of view above discussed without special difficulty. In the roughest outlines, therefore, clinical experience and anatomical findings in dementia praecox may with certain presuppositions be brought into agreement to some extent. It must naturally be left to the future to decide whether and how far such considerations stand the test of increasing knowledge.

CHAPTER IX. FREQUENCY AND CAUSES

Dementia praecox is without doubt one of the most frequent of all forms of insanity. Its share in the admissions to a mental hospital is naturally subject to very considerable fluctuations, not only according to the delimitation of the morbid picture, but also specially according to the conditions of admission. With us approximately 10 per cent. of the admissions might belong to it, while the proportion in Heidelberg amounted to nearly 15 per cent., because there, through formalities which made things difficult, a large number of slight cases of other kinds were kept out. Albrecht states the frequency for Treptow at 29 per cent.; to the real mental hospitals only those patients go, who are absolutely in need of institutional treatment, and the cases of dementia praecox are in the first ranks of these. As the patients neither quickly die off like the paralytics, nor become in considerable number again fit for discharge like the manic-depressive cases, they accumulate more and more in the institutions and thus impress on the whole life of the institution its peculiar stamp. In the private institutions with a smaller number of admissions the share of our patients may in the total amount rise to 70 or 80 per cent.

The Causes of Dementia Praecox

The causes of dementia praecox are at the present time still wrapped in impenetrable darkness. Indubitably certain relations to age exist. The very great majority of cases begin in the second or third decade; 57 per cent. of the cases made use of in the clinical description began before the twenty-fifth year. This great predisposition of youth led Hecker to the name hebephrenia, “insanity of youth,” for the group delimited by him; Clouston also, who spoke of an “adolescent insanity,” had evidently before everything dementia praecox in view, although he did not yet separate it from the manic-depressive type